In my previous post , I introduced Lance’s multi-base layout and how it enables datasets to span multiple storage locations while preserving portability. That design wasn’t just about distributing data across buckets. It laid the foundation for something more powerful: a unified approach to branching, tagging, and shallow cloning.

These features are essential for modern ML/AI workflows. Data scientists need to experiment on production datasets without risking corruption. ML engineers need reproducible snapshots for model training. Platform teams need to manage dataset lifecycles across environments. Different table formats have taken different approaches to these problems, and having designed branching and tagging for Apache Iceberg, I’ve spent years thinking about what works, what doesn’t, and what we can do better.

This post traces the evolution from Iceberg’s snapshot-based branching, to Delta Lake’s shallow clone, and finally to Lance’s unified design that builds on multi-base to deliver both paradigms with maximum flexibility.

The Iceberg Journey: Snapshot Lifecycle Management

In 2021, I authored the original design for Apache Iceberg Snapshot Lifecycle Management , which introduced branching and tagging to Iceberg.

How Iceberg Implements Branching and Tagging

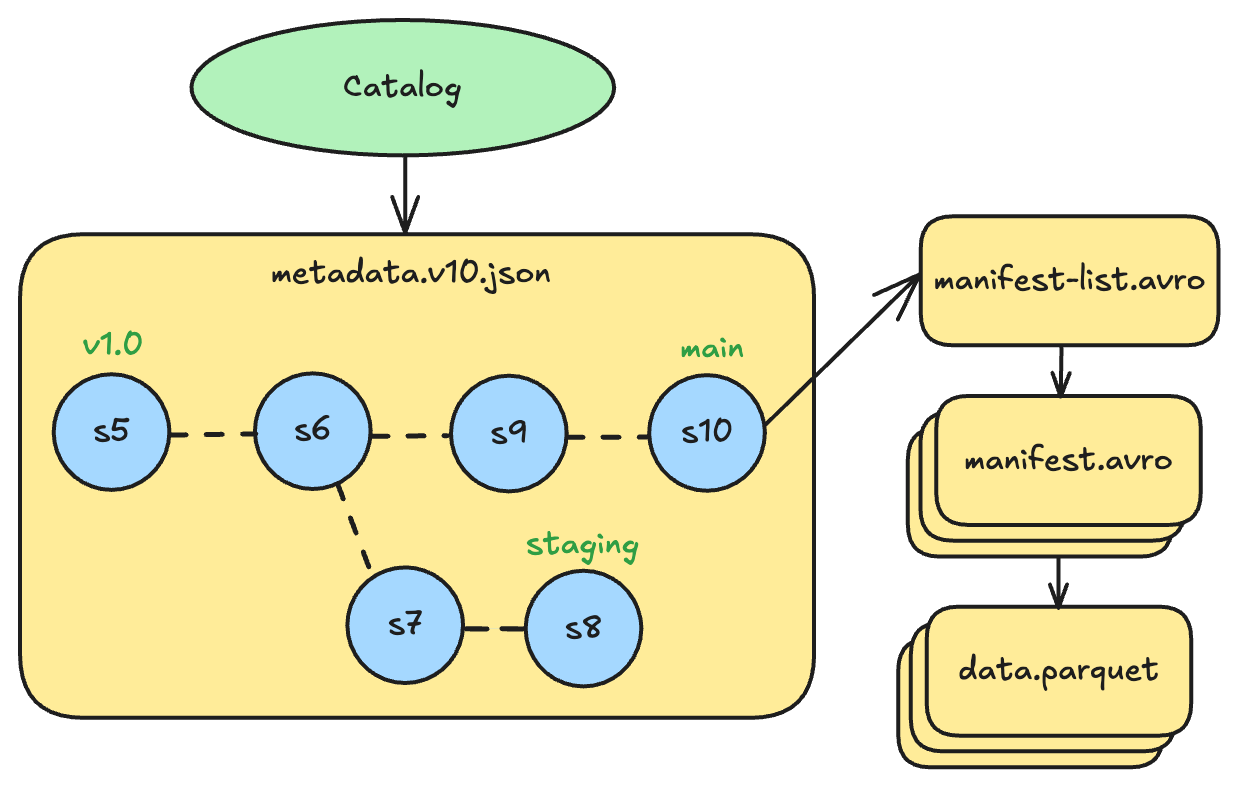

Iceberg’s implementation is structurally similar to Git. The table metadata file maintains a map of named references, where each ref points to a snapshot ID. Branches are refs that point to the head snapshot of that branch. Tags are refs that point to a specific snapshot to preserve it from cleanup.

Every table has a main branch by default. For example, a table might have:

mainbranch pointing to snapshot 10 (the latest production version)stagingbranch pointing to snapshot 8 (diverged earlier for testing)v1.0tag pointing to snapshot 5 (a release checkpoint)

Goals

The Iceberg design had three core goals:

- Decouple time travel from table cleanup. Time travel is a huge selling point for table formats, but it’s not as powerful as it sounds in production. Before branching and tagging, snapshot expiration was the only way to control which historical versions remained accessible. This created a tension: you wanted to aggressively clean up old snapshots because Iceberg’s table metadata size grows proportionally with the number of historical commits, so keeping the number of snapshots low is critical for good performance. But you also wanted to preserve certain versions for auditing, compliance, or reproducibility. Tags solved this by letting users mark specific snapshots as important, exempting them from cleanup regardless of age.

- Make write-audit-publish workflows more useful. Iceberg already had a concept of “staged” commits, but it was limited to a single pending change. Branches extended this to support full workflows where changes could be accumulated, reviewed, and tested before being merged into the main table. QA teams back in the day (and AI agents today) could validate a day’s worth of incremental writes on a branch before publishing to production.

- Enable fast experimentation for ML/AI workloads. This was the critical goal: let data scientists create branches to experiment with transformations, feature engineering, or data augmentation without affecting the production table. Fast, traceable, cost-efficient experimentation at scale. Run experiments in isolation, keep what works, discard what doesn’t.

Problems

Looking back, I believe the design achieved the first two goals well. Tags became widely adopted for marking release versions, compliance checkpoints, and rollback targets. Branching enabled sophisticated data pipelines with staging and validation steps.

But the third goal of ML/AI experimentation was only half-solved. And that limitation taught me something important about table format design.

Problem 1: Performance Bottleneck

The first fundamental issue is performance. Every operation on any branch - creating it, committing to it, or deleting it - updates the root table metadata file. This means all branches share the same metadata file, and any commit to any branch creates a new version of that metadata file. This creates serious problems for ML/AI experimentation workflows:

- Experimental writes can conflict with production commits to the same table metadata

- Production read metadata caches get invalidated with every experimental commit

If a data scientist creates a branch for high-frequency experimentation, every write to that branch can cause commit conflicts with production writes and keep invalidating production read caches. The branches are coupled at the metadata level, and experimental activity degrades production performance.

Problem 2: Weak Governance Isolation

The second issue is that branches share the same table directory and metadata as the main branch, offering no physical isolation between production data and experimental work. All data files, whether written by production pipelines or experimental branches, live in the same location under the same access controls.

This makes it impossible to enforce fine-grained boundaries such as read-only access to production data with write-only access to a branch. A misconfigured or buggy experimental write could tamper with production data, and there is no mechanism at the storage layer to prevent it. In environments where data integrity is critical, this lack of isolation is a serious concern.

Problem 3: Poor Observability and Cost Attribution

Similar to the governance isolation problem, audit logging and cost attribution become difficult when branches share the same table directory. Production queries and experimental queries hit the same data files, making it hard to distinguish their access patterns in audit logs. Storage consumed by experimental branches is attributed to the production table’s budget, with no straightforward way to track costs per branch.

These systems would need to understand branches as a first-class sub-table construct to provide meaningful insights, but the ecosystem is built around tables as the unit of observability.

The Result: Low Ecosystem Adoption

Together, these three problems have made it practically impossible for the ecosystem to build robust tooling around Iceberg’s branching model against a generic Iceberg table. Even if vendors wanted to support branch-level governance and observability, the underlying architecture works against them: you cannot enforce storage-level isolation when all branches share the same directory, and you cannot attribute costs per branch when everything is mixed together at the file level.

As a result, even with Iceberg being the dominant analytical table format today, the adoption of branching and tagging for ML/AI experimentation remains low.

The Delta Journey: Shallow Clone

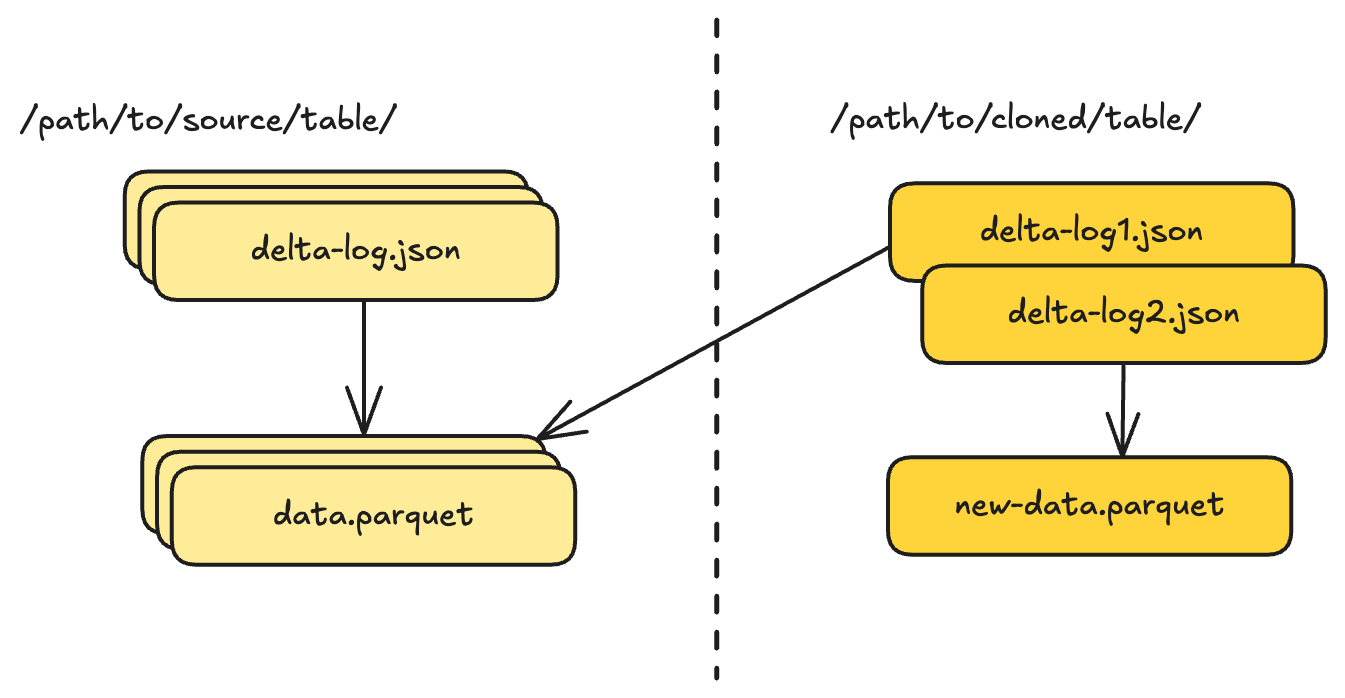

Delta Lake took a different approach with shallow clone , introduced in late 2022. Instead of creating tags and branches within a table, shallow clone creates an entirely new table that references data files from the source.

This is made possible by Delta’s support for absolute paths in its transaction log, as we mentioned in the previous post . While a normal Delta table uses relative paths to reference data files under its own directory, a shallow clone records absolute paths pointing back to the source table’s data files. Any new data written to the clone goes to the clone’s own location using relative paths. This gives the clone its own identity while avoiding a full data copy.

The cloned table:

- Has its own location and identity

- Can be governed independently (permissions, quotas, auditing)

- Shares no metadata with the source after creation

- Can diverge arbitrarily through appends, updates, or schema changes

This elegantly sidesteps the problems in Iceberg. Want to give a data scientist experimentation space? Create a shallow clone. The clone is a first-class table that plugs into existing governance infrastructure. When experiments succeed, migrate the changes back. When they fail, just delete the clone, since it’s just another table.

For several years, I was convinced that shallow clone was the better model for ML/AI experimentation. By creating a separate table, it sidestepped all three problems at once: no commit coupling with production, clean storage-level isolation, and straightforward observability and cost attribution.

Perspective Shift: The Same Requirement in Lance

My thinking changed when both ByteDance and Netflix independently came to me with the same request: they wanted branching in Lance to support their AI experimentation use cases. Coincidentally, both teams’ views had converged on why branching was the right model, and they highlighted a few key benefits:

- Auto-traceability. Branches are always associated with a parent table, so traceability and lineage tracking come out of the box. You don’t need an extra lineage framework to connect an experiment back to its source data, because the relationship is structural, not reconstructed after the fact.

- Simpler data management. All data for a dataset still lives within the same table, making lifecycle management straightforward. Cleanup works against expiration policies defined on branches and tags, with no need to track extra cloned datasets scattered across locations, and no risk of accidentally breaking GDPR compliance by losing track of a clone.

- Intuitive developer experience. ML/AI engineers are developers too. Branching and tagging as Git-native concepts are immediately intuitive: create a branch, experiment, merge or discard. It’s a far better user experience than managing a web of shallow clones.

These conversations made me think hard: is there a way to get the best of both worlds? Could we design a branching solution that preserves all the benefits of branching while also delivering the isolation, governance, and observability that make shallow clone attractive? Could we remove all the problems instead of choosing which set of tradeoffs to live with?

With the help of the Lance community, I believe we’ve found the answer.

Unifying Branching, Tagging, and Shallow Clone With Lance

When we designed Lance’s approach to version management, we had the benefit of hindsight from both Iceberg and Delta. We also had the multi-base architecture already in place, which turned out to be the perfect foundation for a unified design. The full specification is available in the Lance Branch and Tag Specification .

Shallow Clone: Multi-Base in Action

The first building block is shallow clone, which is a direct application of the multi-base layout introduced in the previous post. A shallow clone creates a new, independent dataset that references data files from the source through multi-base path resolution:

Source dataset: s3://production/main-dataset

Clone dataset: s3://experiments/test-variant

Clone manifest base_paths:

[

{ id: 0, is_dataset_root: true,

path: "s3://experiments/test-variant" },

{ id: 1, is_dataset_root: true,

path: "s3://production/main-dataset",

name: "source" }

]

Original fragments (inherited from source):

DataFile { path: "fragment-0.lance", base_id: 1 }

→ resolves to: s3://production/main-dataset/data/fragment-0.lance

New fragments (clone-specific):

DataFile { path: "fragment-new.lance", base_id: 0 }

→ resolves to: s3://experiments/test-variant/data/fragment-new.lanceThe clone is a fully independent dataset with its own location, metadata, and version history. It references the source data through a base path, and any new writes go to the clone’s own directory. No data is copied, only metadata is created.

This is conceptually the same as Delta Lake’s shallow clone, but with more efficient path management. Instead of recording full absolute paths for every inherited file, Lance uses a single base path entry in the manifest to resolve all inherited fragments. The result is the same isolation and independence, with smaller metadata.

Tags: Immutable Global References

The second building block is tagging. Tags in Lance are immutable, named pointers to specific versions. Once created, a tag never changes. It is a global concept that lives outside the version timeline. Tags are invariant under time travel and version rollback: even if you roll the dataset back to an earlier version, all tags remain intact and accessible.

{

"branch": "feature-a",

"version": 3,

"manifest_size": 4096

}Tags are stored under _refs/tags/ at the dataset root and can reference any version on any branch. Tagged versions are exempt from garbage collection, ensuring they remain accessible even as the table evolves.

This is conceptually the same as Iceberg’s tagging, but with stronger invariant guarantees. In Iceberg, tags are stored inside the table metadata file, which means they are subject to operations like rollback that replace the metadata. In Lance, because information can be spread across storage within a location rather than consolidated in a single metadata file, tags live in their own independent files and are never affected by metadata-level operations on the table.

Branching: Shallow Clone + Tagging

With shallow clone and tagging in place, branching falls out naturally as a combination of both: a branch is essentially a shallow clone that lives within the source dataset, plus a tag-like reference recording where it forked from.

The key insight is that branches and shallow clones are conceptually very similar: they’re both datasets that reference data from a source. The difference is simply where they live:

- A branch lives inside the source dataset’s directory structure

- A shallow clone lives at an independent location

One significant departure from Iceberg’s design is how Lance tracks branches. In Iceberg, branches are tracked by their head snapshot ID in the main table’s metadata. Every commit to any branch updates the root table metadata. This is also the root cause of why commits to branches can impact main branch performance, and why data files in a branch are written into the same data location as the main table.

We decided to let Lance track branches by root, not by head. This is a departure from a strict Git-style implementation where branches are tracked by their head commit, but it turns out to be a much better fit for version control in a table format that can track petabytes of data with millions of files. Each branch has its own manifest versions in its own directory in tree/<branch_name>:

{dataset_root}/

_refs/

branches/

feature-a.json # Branch metadata only

tree/

feature-a/ # Branch directory

_versions/

1.manifest # Branch's own version history

2.manifest

data/

*.lance # Branch's own data files

_transactions/

*.txn

_deletions/

*.arrowThe branch metadata file (feature-a.json) records only the branch’s creation point: which version of which parent branch it forked from. All subsequent commits to the branch happen independently in the branch’s own directory.

{

"parent_branch": null,

"parent_version": 5,

"created_at": 1706547200,

"manifest_size": 4096

}The parent_branch field is null for branches created from main, or contains the parent branch name for nested branches. This enables branching from branches, creating hierarchical experimentation workflows.

Under the hood, when you create a branch, Lance:

- Creates a branch metadata file at

_refs/branches/{branch_name}.json, recording the parent branch and version - Creates a new manifest in

tree/{branch_name}/_versions/ - The manifest contains a base path pointing to the parent dataset root

- All fragments from the parent are referenced via this base path

- New writes to the branch create fragments with no base_id (stored locally in

tree/{branch_name}/data/)

Here’s what the multi-base setup looks like for a branch:

Source dataset: s3://data/my-dataset

Branch manifest base_paths:

[

{ id: 0,

is_dataset_root: true,

path: "s3://data/my-dataset",

name: "parent"

}

]

Original fragments (inherited from parent):

DataFile { path: "fragment-0.lance", base_id: 0 }

→ resolves to: s3://data/my-dataset/data/fragment-0.lance

New fragments (branch-specific):

DataFile { path: "fragment-1.lance" } // no base_id

→ resolves to: s3://data/my-dataset/tree/feature-a/data/fragment-1.lanceThis design directly addresses all three problems from the Iceberg design:

- No performance bottleneck. Writes to a branch never touch the main branch’s metadata, so there are no commit conflicts between branches and production, and no cache invalidation from experimental activity.

- Strong governance isolation. Branch data lives in its own directory (

tree/<branch_name>/), physically separated from production data. Storage-level access controls can enforce read-only on the main dataset and write-only on the branch directory. - Clear observability and cost attribution. Because each branch writes to its own directory, audit logs can distinguish branch activity from production activity, and storage costs can be attributed per branch.

It also brings an additional benefit: time travel within branches. In Iceberg, only the main branch maintains a lineage of previous snapshots. Branches are just pointers to a single snapshot, so there is no way to time travel within a branch. In Lance, each branch maintains its own complete version history, giving you full time travel capability on every branch.

Working with Branches, Tags, and Shallow Clone

Let’s look at how these features work in practice with Python examples.

Creating and Using Tags

import lance

import pyarrow as pa

# Create a dataset

data = pa.table({"id": range(1000), "feature": range(1000)})

ds = lance.write_dataset(data, "s3://bucket/my-dataset")

# Add more data

more_data = pa.table({"id": range(1000, 2000), "feature": range(1000, 2000)})

ds = lance.write_dataset(more_data, ds, mode="append")

# Tag version 1 as our baseline

ds.tags.create("baseline", 1)

# Tag current version for model training

ds.tags.create("training-v1", ds.version)

# List all tags

print(ds.tags.list())

# {'baseline': {'version': 1, 'branch': None, ...},

# 'training-v1': {'version': 2, 'branch': None, ...}}

# Access data at a tagged version

ds_baseline = ds.checkout_version("baseline")

print(len(ds_baseline.to_table())) # 1000 rowsCreating and Using Branches

import lance

import pyarrow as pa

# Open the production dataset

ds = lance.dataset("s3://bucket/my-dataset")

# Create a branch for experimentation

experiment = ds.create_branch("feature-experiment")

# The branch starts with the same data as main

print(experiment.version) # Branch-local version (e.g., 1)

print(len(experiment.to_table())) # 2000 rows (same as main)

# Add experimental data to the branch

experimental_data = pa.table({

"id": range(2000, 3000),

"feature": [x * 2 for x in range(1000)] # Different feature engineering

})

experiment = lance.write_dataset(experimental_data, experiment, mode="append")

# Branch has new data, main is unchanged

print(len(experiment.to_table())) # 3000 rows

print(len(ds.to_table())) # Still 2000 rows

# Create nested branches for A/B testing

variant_a = experiment.create_branch("variant-a")

variant_b = experiment.create_branch("variant-b")

# List all branches

print(ds.branches.list())

# {'feature-experiment': {'parent_branch': None, 'parent_version': 2, ...},

# 'variant-a': {'parent_branch': 'feature-experiment', 'parent_version': 2, ...},

# 'variant-b': {'parent_branch': 'feature-experiment', 'parent_version': 2, ...}}

# Switch between branches (None is equivalent to the latest version in the branch)

ds_variant_a = ds.checkout_version(("variant-a", None))

# Write to the branch

variant_a_data = pa.table({

"id": range(3000, 4000),

"feature": [x * 3 for x in range(1000)]

})

ds_variant_a = lance.write_dataset(variant_a_data, ds_variant_a, mode="append")

# Read from the branch

print(len(ds_variant_a.to_table())) # 4000 rows

print(len(ds.to_table())) # Still 2000 rows on mainCreating Shallow Clones

import lance

import pyarrow as pa

# Clone from production to experimentation environment

ds = lance.dataset("s3://production/main-dataset")

# Clone the latest version

clone = ds.shallow_clone(

"s3://experiments/clone-latest",

ds.version

)

# Clone a specific tagged version

clone_baseline = ds.shallow_clone(

"s3://experiments/clone-baseline",

"training-v1" # Reference by tag name

)

# Clone from a branch

branch = ds.checkout_version(("feature-experiment", None))

clone_from_branch = branch.shallow_clone(

"s3://experiments/clone-experiment",

branch.version

)

# The clone is a fully independent dataset

clone.tags.create("clone-baseline", 1)

new_data = pa.table({"id": [4000], "feature": [12345]})

clone = lance.write_dataset(new_data, clone, mode="append")Future Vision: lance-git

Looking back at my Iceberg branching and tagging design, I now see that the experience it provided was very much like SVN : a centralized model where all branches funnel through a single metadata file, with no real isolation or independent history. With Lance’s design, however, we are moving toward a true “Git-like” experience: distributed, isolated branches with independent version histories, and the ability to work across local and remote storage seamlessly.

I see all the foundational components needed to deliver that experience:

- Multi-base is the key enabler for data to live partially in local storage and partially in remote storage, just like a Git repository with local and remote refs.

- Shallow clone represents a mechanism similar to

git fetch: it can pull partial metadata to a local or separate location without copying the underlying data, giving you a working dataset that references the remote source. - Branches and tags are the essential core user experience primitives that make Git intuitive for developers, and they translate directly to dataset version control with the same semantics.

Consider a common scenario: you have a Lance dataset in cloud storage and want a Git-like experience locally. Here’s how the primitives map:

| Git | Lance | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Repository | Dataset | The unit of version control |

| Remote | Base path to cloud storage | The cloud location where the dataset lives (e.g. s3://production/dataset) |

| Clone | Shallow clone to local | Copy metadata to a local directory, reference cloud data via multi-base |

| Fetch | Shallow clone (partial) | Pull latest metadata from cloud without copying data files |

| Pull | Fetch + merge | Fetch latest metadata and integrate new versions into the local dataset |

| Commit | Version | Record a new point-in-time snapshot on the current branch |

| Branch | Branch | Create an isolated line of development, locally or in cloud |

| Tag | Tag | Create an immutable named reference to a specific version |

| Checkout | Checkout branch/version | Switch to a specific branch or version for reading and writing |

| Push | Write to remote base | Upload local branch data and metadata back to cloud storage |

| Log | Version history | View the version history of a branch |

What’s missing is the user experience layer: the familiar commands and workflows that make Git intuitive. I’m very interested in creating a lance-git subproject to fully explore this space:

# Initialize a new lance repository

lance-git init s3://bucket/my-data

# Clone an existing dataset

lance-git clone s3://production/dataset ./local-copy

# Create a branch for experimentation

lance-git branch experiment

# Switch to the branch

lance-git checkout experiment

# See version history

lance-git log

# Tag a version

lance-git tag v1.0.0

# Fetch latest metadata from remote

lance-git fetch origin

# Pull and integrate remote changes

lance-git pull origin main

# Push changes to remote

lance-git push origin experimentThe goal isn’t to exactly replicate Git: data has different semantics than code. But the mental model of distributed version control is powerful, and there have been many attempts to bring it to data at various layers, such as Nessie as a catalog-level versioning system, lakeFS as a storage-level Git layer, and Bauplan as a versioned data pipeline platform. I truly believe the table format is the right layer to solve this problem at, because it is the layer that owns the data layout, metadata structure, and file lifecycle. Version control at any other layer means working around the format rather than with it. With the primitives we’ve built in Lance, I think we’ve achieved that foundation.

If anyone in the community is interested in collaborating on lance-git, I’d love to hear from you. The primitives are in place; it’s now time to build the experience.

Acknowledgments

This work wouldn’t have been possible without Nathan Ma from ByteDance, who co-designed the branching and shallow clone system with me and drove all the implementation to completion. Special thanks to Pablo Delgado and Bryan Keller from Netflix for the invaluable feedback that guided us to this design.

Conclusion

Table format version management has evolved through distinct phases:

- Iceberg introduced branching and tagging within tables, solving write-audit-publish and time travel use cases well. But for ML/AI experimentation, it hit three fundamental problems: commit-level coupling degrading production performance, weak governance isolation risking data integrity, and poor observability when everything is mixed at the file level.

- Delta Lake introduced shallow clone as independent tables, sidestepping all three problems by creating a separate table. But it lost the benefits of branching: auto-traceability, simple data management, and the intuitive Git-like developer experience.

- Lance unifies both approaches on top of multi-base. Shallow clone uses multi-base for efficient cross-location data referencing. Tags provide immutable global references with stronger invariants than Iceberg. Branching combines both primitives, tracking by root rather than head to deliver commit isolation, strong governance, and clear cost attribution, while preserving the traceability and intuitive UX that make branching compelling.

For ML/AI teams, this means you can:

- Use tags to mark training data snapshots and model versions, with immutable guarantees that survive rollback

- Use branches for fast, isolated experimentation with full time travel, strong governance, and per-branch cost attribution

- Use shallow clones when you need hard isolation, independent lifecycle management, or cross-team collaboration

All built on a portable, open format that you can move between clouds without rewriting metadata. And with the foundational primitives in place, we see a clear path toward a full Git-like experience for datasets.